The Natural Exponential Function

The definition. The natural logarithm function ln x

is an increasing function whose domain

is the open interval (0,∞) and whose range is R, all of the real numbers. Since

it’s increasing,

therefore it’s one-to-one and has an inverse, the natural exponential function,

which we denote

exp x. Soon we’ll also denote it ex, but as that notation already has

a meaning when x is a

rational number, we’ll have to show exp x agrees with ex for rational

x.

Now, exp is inverse to ln, and that means

exp x = y iff x = ln y.

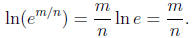

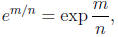

Let’s start by showing exp(m/n) = em/n for rational numbers m/n so we

can use the

usual exponential notation. We know that

But since exp is inverse to ln, that statement is equivalent to

which is what we wanted to show.

Now we can use the usual exponential notation, but be aware that exp is still

used when

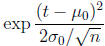

the exponent is complicated. For instance, a notation like

is preferred by many

is preferred by many

over  .

.

Properties of the natural exponential function. That the natural

exponential function

is inverse to the natural log now reads

| ex = y iff x = ln y |

From this logical equivalence, every statement about ln

can be converted to a statement

about ex.

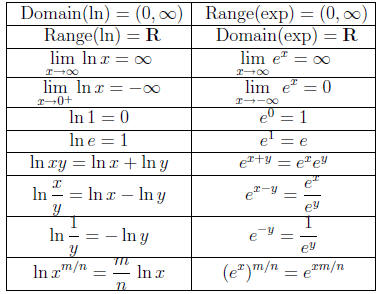

Here’s a table with properties of ln and exp.

The first few lines in the table are direct translations

of the properties of ln into properties

of exp. The later ones are almost direct, but not quite. For example, let’s see

how the identity

ln xy = ln x+ln y implies the identity  . It

would help to change the variables in one

. It

would help to change the variables in one

of the identities since they don’t exactly correspond. Let’s show the identity

ln xy = ln x+ln y

implies the identity  .

.

Let s = ln x so that x = es, and let t = ln y so that y = et.

Since ln xy = ln x + ln y,

therefore s + t = ln x + ln y = ln xy. That implies

, which equals eset,

and that was

, which equals eset,

and that was

what we wanted to show.

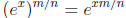

Note that the final equation in the right column of the table,

is not quite

is not quite

satisfactory. We would prefer to have  for

any real number y, not just for rational

for

any real number y, not just for rational

y = m/n, but we haven’t yet defined what  would mean since we have only defined

would mean since we have only defined

exponentiation when the base is e, not when the base is an arbitrary real number

like ex.

That comes soon.

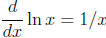

The derivative and integral of the natural exponential function. Recall

that, for

positive x,  , that is,

, that is,

. Let’s use that information to determine

. Let’s use that information to determine

the derivative and integral of ex. We’ll use the inverse function

theorem for derivatives to to

that.

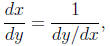

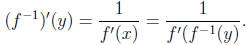

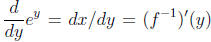

The inverse function theorem says that if y = f(x) so that x = f -1(y),

then

that is,

Right now, we have y = f(x) = ln x, x = f -1(y)

= ey, and f'(x) = 1/x. We want to find the

derivative of ey, that is,  . By

the inverse function theorem, that

. By

the inverse function theorem, that

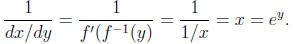

equals

Thus, the derivative  of the exponential function ey is itself ey. If we switch

to x as the

of the exponential function ey is itself ey. If we switch

to x as the

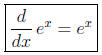

independent variable, we can write this result as the exponential rule for

derivatives

It is this property of the exponential function that gives

it lots of applications in science.

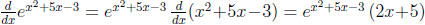

Frequently, an exponential function has an exponent that is not just the

variable x, but

a function of x, for instance  . To find its

derivative, use the exponential rule for

. To find its

derivative, use the exponential rule for

derivatives along with the chain rule:

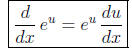

More generally,

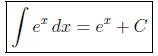

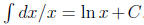

We can immediately use the exponential rule for

derivatives,  , to integrate the

, to integrate the

exponential function.